3 Most Important Ethical Issues in Journalism

At its core, journalism is defined as a public service—an institution committed to maintaining the good of the public. This requires journalists to uphold an ethical and moral standard when executing their practice. Especially today, with distrust in the media at an all-time high and technology changing the role of the traditional journalist, it’s necessary to turn to ethics to maintain credibility and a healthy democracy.

Furthermore, adhering to ethical standards, such as those laid out in the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) Code of Ethics, helps diminish individual or corporate agendas and protects the well-being of fellow and future journalists.

For these reasons, I deem three ethical issues to be the most important in helping adhere to the SPJ Code of Ethics and protecting a journalist’s duty to the public: Acknowledging the importance of limiting the First Amendment through unfree speech, enforcing source safety, and protection, and prioritizing the perspectives and experiences of people affected through solidarity reporting.

Limitations to the First Amendment

The First Amendment is an essential ruling in the world of journalism, as it not only protects journalists and sources as they express their free ideas, but ensures that the government cannot interfere with the content of news reporting. Yet, to maintain social order and protect the peace of certain individuals, I argue that journalists need to be more aware of the limitations on free speech and how it’s beneficial for democracy. When examining the exact wording of the First Amendment, it states that “Congress shall make no law” prohibiting free speech, press, or assembly. However, in order to protect public safety and preserve national security, Congress has created categories of unfree speech including “the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words—those of which inflict injury or breach of the peace” as exceptions to the First Amendment. It’s vital for journalists to understand these limitations in order to avoid defamation in their reporting and act responsibly in the public interest. Consequences for a breach of these limitations can be seen in cases such as the Alex Jones and Sandy Hook defamation suits.

Radio show host and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones was faced with defamation lawsuits after claiming that the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting was a hoax. The parents of the victims claimed that his lies led to threats, harassment, and emotional distress. Jones used the First Amendment as his defense, stating that “if questioning public events and free speech is banned because it might hurt somebody’s feelings, we are not in America anymore.” First Amendment absolutists like Alex Jones go against journalism’s basic values of “acting with integrity” and building a “foundation of democracy” as written in the SPJ Code of Ethics.

Ultimately, the parents of the Sandy Hook victims used a libel law defense to win the case, totaling Jones’ damages to around $49 million. Libel, a published statement that damages a person’s reputation, contains seven elements that must be proven in order for a statement to be classified as libelous. Indeed, libel is often difficult to prove because the First Amendment requires strict clarification, but it is also crucial in holding journalists accountable for what they publish.

Therefore, because publishing unfree speech can bring harm to both journalists and the public, I believe that a limited First Amendment is a necessary ethical issue for journalists to remember.

Source Protection

Just as the public relies on the media for accurate information, journalists rely on their sources for their expertise, experiences, and emotions. This mutually beneficial relationship makes source protection another vital ethical issue in journalism.

However, when looking at the SPJ Code of Ethics, certain wording seems to contradict the importance of source protection. While one section of the code states that it’s a journalist’s duty to “minimize harm” for their sources, another section tells journalists to “act independently” of special interest or conflicts. Despite this, source protection is vital in preserving source retention as it provides them comfort when sharing necessary, sensitive information.

In journalist Natalie Yahr’s Guide to Less-Extractive Reporting, she discusses twelve rules for sourcing in an effort to share the importance of a “more mutually beneficial journalism.” For instance, in Yahr’s “Rule #2: Don’t mislead or confuse your sources,” she discourages lying or giving false hope to sources. Additionally, Yahr encourages journalists to make sources as comfortable and in-control as possible through “Rule #5: Use research and planning as tools of sensitivity” and “Rule #4: Look for ways to give your sources some editorial control.”

I agree with Yahr in that minimizing the harm of those we serve is a larger ethical responsibility to uphold than acting independently, while there are certainly instances when revealing a source is necessary for legal or national security reasons. However, I argue that in order to form more accurate stories in the long run, journalistic integrity and trust should be a priority, especially when there are options for anonymity or pseudonyms.

Solidarity Reporting

Journalism has the unique opportunity to change the world for the better by giving a voice to marginalized groups. Through solidarity reporting, journalists not only make a commitment to social justice that translates into action but ultimately contribute to more accurate reporting.

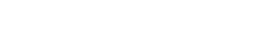

In Anita Varma’s Solidarity Reporting Guide, she calls attention to the issue in today’s more dominant reporting practices that focus on elites and officials while forcing the perspectives of marginalized people to the sidelines. She brings up examples of articles that follow solidarity reporting practices, such as an Austin American-Statesman article that covers an abortion rights rally from the perspectives of the protestors rather than government officials. Stories like these can “help a broader public understand social injustice and what can be done about it,” according to Varma.

Furthermore, solidarity reporting forces a journalist to consider newsworthiness, sourcing, framing, interviewing, and impact—all of which contribute to an accurate story. Despite being necessary, these categories are often ignored or neglected, so Varma reminds us that “with solidarity reporting, a story is newsworthy if it involves a community whose basic humanity is being disrespected or denied.”

Therefore, I believe that, when possible, solidarity reporting is the most important form of reporting, as it contributes to the good of the public by advocating for marginalized groups and placing those in power accountable for their actions.

Conclusion

With new advancements in social media, and the internet changing the role of the traditional journalist, ethical journalism is more important than ever in upholding the credibility of the media industry. The First Amendment provides the foundation for our craft, but it’s vital for journalists to understand that its limitations can sometimes better serve our ethical purpose. Additionally, making the safety and well-being of our sources a priority minimizes harm to those we rely on for our stories. Finally, solidarity reporting not only advocates for the public we serve but leads to more accurate reporting practices. Though I deem these issues the most important, ethical journalism is a vital conversation to be had in all newsrooms and, as written in the SPJ Code of Ethics, should “encourage all who engage in journalism to take responsibility for the information they provide.”